When you send us a file to be printed, it’s helpful to understand proper resolution. Printed images require much higher resolutions than on-screen images, and it’s best to have the proper settings from the beginning — because while we can always make the image smaller, we cannot go up in size without losing quality. To achieve a crisp, clear, and detailed final product, here’s what you need to know.

important terms

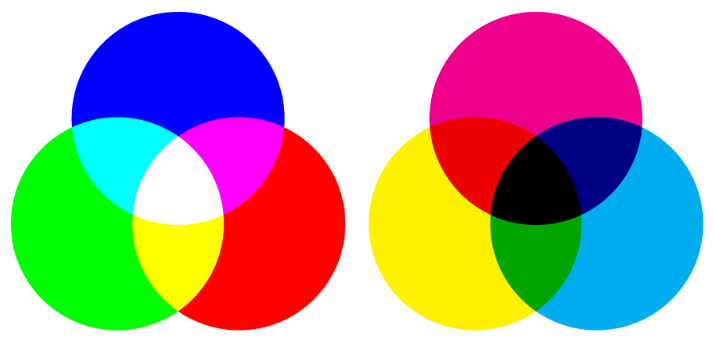

The DPI is the number of dots in a printed inch. The larger the DPI number, the greater the resolution, which means you’ll be able to see more detail. Printers produce images with tiny dots that mix CMYK colors, and the more dots per inch — or the less space there is between these dots — the crisper your final product will be.

You may also see the term PPI used, which stands for “pixels per inch.” PPI typically refers to on-screen images, whereas DPI applies to printing, but some people use them interchangeably.

how to set your DPI

You can set your DPI by changing the “Resolution” number when creating a new file in Photoshop. 300DPI is the standard for most high-quality prints, and 150DPI is generally the minimum.

(While you’re here, make sure you’re using the proper color mode and that the canvas dimensions are not too small for your print job. As stated above, it’s hard to go up in size without losing quality, so a file for a poster print, for example, should not be 2x5”.)

web vs. print

Web images typically have smaller resolutions, in order to allow for faster load times. It’s not really necessary to have a high resolution for web — the quality looks fine at 72DPI, which is the standard. So basically, you may want to have two separate files for print and web that are optimized accordingly.

in conclusion...

Always keep in mind that digital and printed images differ in a number of ways. A detailed, high-quality on-screen image will not necessarily translate well to print. If the resolution is too small, the final product may appear blurry or pixelated.

Again, it’s best to use the proper settings from the beginning, when you first create your file. Contact us if you have any questions.